GStreamer, Go, and Kubernetes

Back when I was working on kvdi (a Kubernetes-native “Virtual Desktop Infrastructure” written in Go), I got to the inevitable point that I wanted support for audio streams from the user desktops. In a web-based VDI solution, this posed several challenges:

- Raw PCM data is huge, and as such is not suitable for streaming over low latency networks.

- To work with browser-native audio APIs, we need either raw PCM or one from a small set of browser supported encodings (WASM opens more doors, but I wanted to avoid it).

- VNC, the protocol serving the user desktop displays, does not have support for audio.

- QEMU Extended Audio exists in the protocol now, but is only implemented by the QEMU VNC server/client.

- While compensating for stream size and having to utilize side channels because of the above, we’d still like to be able to achieve near real-time playback.

- WebRTC can shine in areas like this, but facilitating the STUN protocol from inside a Kubernetes cluster was not an adventure I wanted to start just yet.

In another blog post I may go over these challenges and how I was able to overcome them in implementation, but that is not the purpose of this article. For now, what’s important is that PulseAudio, GStreamer, webm/opus, and websockets saved the day. The first implementation was accomplished entirely through subprocesses and redirecting shell pipes, but this is a poor way to write code and an almost insulting way to utilize the true power of the GStreamer API 😛.

Unfortunately, there didn’t exist any truly comprehensive and feature-complete Go bindings for GStreamer, or at least any that implemented all of the APIs I needed to accomplish my goal. And so, go-gst, and later go-glib were forked and born. I started from the excellent work done by the gotk3 project, and then saw the rest of the GStreamer API bindings to pseudo-completion (these bindings remain actively developed with some help starting to come in from the community).

Fast forward a bit (and with huge thanks to slomo from the GStreamer team and his fantastic write up on exporting GObject APIs from Rust), I found myself with the ability to write full GStreamer applications (and plugins!) entirely in Go. I’ll likely do another writeup in the future on the adventure of exporting GObjects from gocode, but for now the only question that remained was, what should I try next? Well since Go, where did that bring me? Right back to Kubernetes.

GStreamer Pipelines on Kubernetes

The idea was simple. Define a CustomResourceDefinition that implements a sort of “yamlized” version of the better-known gst-launch-1.0 from the GStreamer tools.

CustomResources using this API could have some arbitrary source destination watched for multimedia files, and have those objects automatically fed through their pipeline.

For source and destinations I chose MinIO first, primarily for the ease with which it can be deployed in development environments.

I started, as I do with almost all of my custom Kubernetes controllers, with the operator-sdk.

Perhaps I’ll do a more in-depth post later on how the APIs and controllers were designed for this use case, but the meat of what I want to cover is in the translation from yaml to dynamic GStreamer pipelines.

In the end, the PoC for a CustomResource implementing one of the APIs looked like this:

The full PoC can be found here: https://github.com/tinyzimmer/gst-pipeline-operator

---

apiVersion: pipelines.gst.io/v1

kind: Transform

metadata:

name: mp4-converter

spec:

# Globals will be merged into the `src` and `sink` configs during processing.

# This is useful if all operations are happening against the same MinIO server

# and buckets. You can also direct output to/from different servers and buckets

# by declaring those values in their respective areas instead of here.

globals:

minio:

endpoint: "minio.default.svc.cluster.local:9000" # The endpoint for the MinIO server

insecureNoTLS: true # Use HTTP

region: us-east-1 # The region of the bucket

bucket: gst-processing # The bucket to watch for files

credentialsSecret: # The secret containing READ credentials for MinIO

name: minio-credentials

src:

minio:

key: drop/ # Watch all files placed in the drop/ prefix

sink:

minio:

key: "mp4/{{ .SrcName }}.mp4" # Generate an output name from this template. If the src file was called

pipeline: # drop/video.mkv then this would evaluate to mp4/video.mp4.

debug:

dot:

path: debug/ # Optionally dump DOT graphs to the debug/ prefix for each pipeline

render: png # Optionally render those DOT graphs to PNG in addition to the DOT format.

# The pipeline definition. This is the "yamlized" version of the gst-launch-1.0 syntax.

elements:

- name: decodebin

alias: dbin # The same as applying a `name` in gst-launch-1.0

- goto: dbin # Take a compatible sink pad from the decodebin

- name: queue

- name: audioconvert

- name: audioresample

- name: voaacenc

- linkto: mux # Link the output of this chain to the `mux` element

- goto: dbin # Go back to the decodebin and take the next compatible sink pad

- name: queue

- name: videoconvert

- name: x264enc

- name: mp4mux # Joins the output from the audio stream and the video stream into an mp4

alias: mux # container.

# The last element evaluated in the pipeline (either in order or via goto/linkto) has its output

# sent to the MinIO output object.

There is obviously a lot happening here besides just the pipeline parsing.

For example, the plugins facilitating the reading and writing to/from MinIO were written using the go-gst bindings as well, but we can table that discussion for another time.

The part I want to focus on is the elements block at the end.

This is where I ventured to mimic (as closely as possible) how this would look in gst-launch-1.0 syntax. A comparable pipeline to the above on the command-line would look like this:

gst-launch-1.0 \

miniosrc location=$object \

! decodebin name="dbin" dbin. ! queue ! videoconvert ! x246enc \

! mp4mux name=mux ! miniosink location=$object.mp4 dbin. \

! queue ! audioconvert ! audioresample ! voaacenc ! mux.

The finished code that parses the yaml (after it has been deserialized) into a GStreamer pipeline can be found here, but we’ll walk through it piece-by-piece.

package main

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

"github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst/gst"

pipelinesmeta "github.com/tinyzimmer/gst-pipeline-operator/apis/meta/v1"

)

func buildPipelineFromCR(cfg *pipelinesmeta.PipelineConfig, srcObject *pipelinesmeta.Object, sinkObjects []*pipelinesmeta.Object) (*gst.Pipeline, error) {

pipeline, err := gst.NewPipeline("")

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

pipelineCfg := cfg.GetElements()

src, err := makeSrcElement(srcObject)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

pipeline.Add(src)

// ...

}

The beginning is pretty straight-forward. First, we create a new GstPipeline with a generated name.

The pipelineCfg is populated with the deserialized contents of the elements block shown above in the CustomResource.

We then make our source MinIO element pointing at the object that triggered this pipeline and add it to the GstPipeline.

Now is where things begin to get exciting. We need to iterate the element configurations provided by the user, and link them up properly in the pipeline. We also need to take into account that the user may have defined elements that are providing dynamic src pads and can’t be linked right away, and we’ll get more into that later.

To start, we’ll declare some pointers outside of the scope of the for loop we are about to do.

// Track a pointer to the last element we iterated on in the pipeline

var last *gst.Element = src

// Track a pointer to the user-supplied configuration defining that last element

// (with some extra metadata we added to help us later)

var lastCfg *pipelinesmeta.GstElementConfig

We can now start looping through our elements:

for _, elementCfg := range pipelineCfg {

// If we are jumping in the pipeline - set the last pointers to the appropriate element and config

if elementCfg.GoTo != "" {

// Retrieve the user configuration for this element from the pipeline config

// and set it to the last pointer.

lastCfg = pipelineCfg.GetByAlias(elementCfg.GoTo)

if lastCfg == nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("No configuration referenced by alias %s", elementCfg.GoTo)

}

// Retrieve the actual gst.Element from the pipeline for this configuration and set it to the

// last pointer. How this function works will be shown below.

last, err = elementForPipeline(pipeline, lastCfg)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Continue on to the next element in the configuration

continue

}

// If we are linking the previous element - perform the links depending on the alias.

// Sets the last pointers as well, but at this point the user is probably doing a goto

// next or this is the end of the pipeline and will be linked directly to the MinIO sink.

if elementCfg.LinkTo != "" {

// Retrieve the configuration for the element we are linking to

thisCfg := pipelineCfg.GetByAlias(elementCfg.LinkTo)

// Retrieve the actual element we are linking to from the pipeline

thisElem, err := elementForPipeline(pipeline, thisCfg)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Perform the link, how this works will be shown below.

if err := linkLast(pipeline, last, lastCfg, thisElem, thisCfg); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Declare the linked-to element as the last element iterated on

last = thisElem

lastCfg = thisCfg

// Continue to the next element in the configuration

continue

}

// Neither of the conditions apply. This is just a regular element block with optional

// properties.

// Retrieve (or create) the element from the pipeline (more details below)

element, err := elementForPipeline(pipeline, elementCfg)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Link to whatever the last pointers are set to

if err := linkLast(pipeline, last, lastCfg, element, elementCfg); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Set this element as the last object iterated on.

last = element

lastCfg = elementCfg

}

// Finally we create the sink element and link it to wherever we ended in the loop.

sink, sinkCfg, err := makeSinkElement(sinkobj)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

pipeline.Add(sink)

if err := linkLast(pipeline, last, lastCfg, sink, sinkCfg); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

The two functions we need to explore a little more in-depth here to truly feel the magic, are elementForPipeline and linkLast.

The way it is utilized above, elementForPipeline needs to be an idempotent GstElement fetcher for us.

That is to say, if the element has not been created and added to the pipeline yet, we want to do so.

However, if it was already created and added to the pipeline, we don’t want to recreate it and just want the original reference back.

How that looked in practice is like this:

func elementForPipeline(pipeline *gst.Pipeline, cfg *pipelinesmeta.GstElementConfig) (thiselem *gst.Element, err error) {

// Below this we set a name to the configuration that we can re-use later when we create

// the element for the first time. This is the name that GStreamer generated and assigned

// to the element when it was first created.

// First check if we have that name set in our configuration.

if name := cfg.GetPipelineName(); name != "" {

// We iterated on this configuration before, and thus already have the element's *real* name

// We can retrieve the element reference directly from the pipeline by that name.

thiselem, err = pipeline.GetElementByName(name)

return

}

// We did not set a name to this configuration, so we must be creating the element for the first time.

// makeElement is a bit of an ugly wrapper around taking the potential properties provided by the user

// and converting them to GValues of the appropriate type based on the element's properties.

thiselem, err = makeElement(cfg)

if err != nil {

return

}

// Add the element to the pipeline

pipeline.Add(thiselem)

// Set the name assigned to the element for later use.

cfg.SetPipelineName(thiselem.GetName())

return

}

The other piece we want to explore is linkLast. Most elements in GStreamer provide static src and sink pads that can be linked

directly while the pipeline is being built. In the go bindings, this is as simple as calling last.Link(this).

However, and in our example above as well, there are some elements that provide dynamic pads. In the example above this is the decodebin element.

I won’t get into the full nitty-gritty of the magic happening underneath the hood in decodebin, but what’s important for now is that when it is first created

it has no idea what sort of input it will be getting. After the stream has started it attempts to detect the formats it received, dynamically creates the necessary

decoding/demuxing elements, and then provides a src pad once it has linked its own elements internally.

It produces signals once it has set up pads it can provide, and the application can tap into those signals with callbacks to do dynamic linking at playtime. With that in mind, let’s look at the code.

func linkLast(pipeline *gst.Pipeline, last *gst.Element, lastCfg *pipelinesmeta.GstElementConfig, element *gst.Element, elementCfg *pipelinesmeta.GstElementConfig) error {

// Check if the last element we are linking to has a static src pad we can link to the

// sink pad on this element. If it does, we are in luck! Just perform the link and return.

// One thing to note is that the API does not yet support defining filter caps for linking.

// The bindings can do this via LinkFiltered, and for now in the K8s API the user can use

// a capsfilter element.

if srcpad := last.GetStaticPad("src"); srcpad != nil {

return last.Link(element)

}

// Unfortunately we don't have static pads. In the example above, "last" currently represents

// the decodebin element.

//

// Similar to how we tracked names in the configurations we were passing around, another field

// is present in the configuration structure that allows us to track peers for later consumption.

// Add the element we are *supposed* to link as a peer to the configuration.

lastCfg.AddPeer(elementCfg)

// We are hoping (which is the case with decodebin at least) that the element will emit the "no-more-pads"

// signal once it has created all the src pads it can provide. We connect to this signal and add a callback

// that will be executed after the pipeline has been started and decodebin has built out its own pipeline.

last.Connect("no-more-pads", func(self *gst.Element) {

// Retrieve all the available pads from the element that emitted this signal

pads, err := self.GetPads()

if err != nil {

self.ErrorMessage(gst.DomainLibrary, gst.LibraryErrorFailed, err.Error(), "")

return

}

// We are now going to loop over the available pads and link them to the appropriate

// elements that are already created and waiting for a friend in the pipeline.

Pads:

for _, srcpad := range pads {

// Skip already linked and non-src pads

if srcpad.IsLinked() || srcpad.Direction() != gst.PadDirectionSource {

continue Pads

}

// Iterate the peers that were registered to the configuration for this element

for _, peer := range lastCfg.GetPeers() {

// Retrieve the actual element from the pipeline using the function we defined

// earlier.

peerElem, err := elementForPipeline(pipeline, peer)

if err != nil {

self.ErrorMessage(gst.DomainLibrary, gst.LibraryErrorFailed, err.Error(), "")

return

}

// Retrieve the sink pad from that element

peersink := peerElem.GetStaticPad("sink")

if peersink == nil {

self.ErrorMessage(gst.DomainLibrary, gst.LibraryErrorFailed, fmt.Sprintf("peer %s does not have a static sink pad", peer.Name), "")

return

}

// If this new src pad can be linked to the sink pad then link it.

// We check CanLink first becuse there may be multiple src pads with

// only specific elements compatible with the media type in them.

if srcpad.CanLink(peersink) {

srcpad.Link(peersink)

continue Pads

}

}

}

})

// We are done here - if we defined a callback it will get fired later.

return nil

}

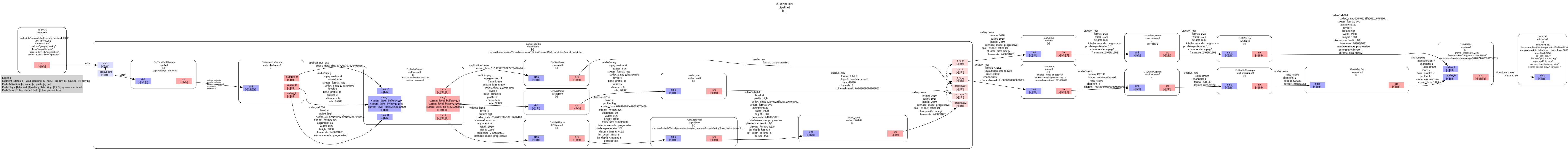

With the above all done (and Kubernetes APIs implemented), we go drop some random MKV into our “drop/” prefix in MinIO and see what gets created. The additional fields on the CustomResource for debugging tell the runner (in areas not covered here) to also dump graphs of what the pipeline ends up looking like.

I recognize you may need to download and zoom to properly view the contents of the image.

We can see here that the MKV I dropped actually already contained H264 video. So we essentially converted it RAW, straight back into H264, and then just slapped it into a different container. But the important thing is that all the linking (both static and dynamic) happened correctly!.

Well that’s all I got for this post. If you found it interesting then stay tuned for my posts in the future, and feel free to hop over to my Github and take a look at this and some of my other GStreamer related projects recently.