Extending GObjects From Go and Making Them Available to C

A journey through implementing GObjects with cgo and making them accessible to C code

When I first started writing my GStreamer bindings for go, I had never done C library bindings before. I had written small programs in C for fun, but most of my professional work was either Go, Python, or just pure BASH. I spent a lot of time over in #gstreamer on freenode probably driving the core developers utterly insane.

About half way through this adventure, I was working on the bindings for one of the APIs (I don’t remember which) and when inquiring further about it slomo informed me “that’s really only used for plugins.” What slomo might not have realized at the time was that I took this as a direct challenge. And he was in for a much more difficult time shaking me off.

I really had no need for plugins in my use-case for the bindings at that moment, so a month or two went by before I revisited the idea. Two or three COVID lockdowns later, I put my head down and got to work. I quickly realized I had bitten off more than I could chew, and it was then that slomo directed me to his incredible post about Exporting GObject C APIs from Rust. If you find this topic interesting, I highly recommend giving it a read. I do go over some of the concepts covered in that article, but no where near as in-depth. While I did not have access to all the same language features as Rust, I used the article as a sort of flexible blueprint while I ventured into making it possible from Go.

This article will end up being very similar in some contexts, and I’ll do my best to avoid completely plagiarizing all the work done there. We’ll walk through some of the core concepts, how I translated them into gocode, and then we can look at a working implementation.

Brief GObject Introduction

I really can’t say it better than slomo’s article linked above myself:

“GObject is a C library that allows to write object-oriented, cross-platform APIs in C (which does not have support for that built-in), and provides a very expressive runtime type system with many features known from languages like Java, C# or C++. It is also used by various C libraries, most notably the cross-platform GTK UI toolkit and the GStreamer multimedia framework. GObject also comes with strong conventions about how an API is supposed to look and behave, which makes it relatively easy to learn new GObject based APIs as compared to generic C libraries that could do anything unexpected.”

For a little more detail on how this works in the context of GStreamer plugins, each plugin is simply a GObject that optionally (though required if you want actual functionality) extends on base objects declared and implemented in the core API.

The plugins are compiled to shared libraries (.so files) and provide metadata from exported symbols that follow a naming convention based on that of the plugin itself.

That metadata, among other things, provides a pointer to the method GStreamer can call to initialize instances of the plugin’s element through the GObject type system.

Go already lets us compile to C shared libraries by using go build -buildmode c-shared. This outputs both an .so file that can be loaded dynamically, and a header file that can be included by C applications wanting to use the library.

The goal was to leverage this and in the end be able to provide an element to GStreamer from gocode with something like this:

package main

import (

"github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst/gst"

"github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst/gst/base"

)

// The metadata for this plugin

var pluginMeta = &gst.PluginMetadata{

MajorVersion: gst.VersionMajor,

MinorVersion: gst.VersionMinor,

Name: "myawesomeplugin",

Description: "My awesome GStreamer plugin written in go",

Version: "v0.0.1",

License: gst.LicenseLGPL,

Source: "go-gst",

Package: "examples",

Origin: "https://github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst",

ReleaseDate: "2021-01-04",

// The init function is called by GStreamer to register elements provided by the plugin.

Init: func(plugin *gst.Plugin) bool {

return gst.RegisterElement(

plugin,

// The name of the element

"goplugin",

// The rank of the element

gst.RankNone,

// The GoElement implementation for the element

&myGoObject{},

// The base subclass this element extends

base.ExtendsBaseSrc,

)

},

}

type myGoObject struct{}

// ...

// VMethod implementations to override from the GstBaseSrc type

// written entirely in Go.

Registering a GType for an Arbitrary Go Object

All of the code referenced throughout this artcle can be found in its finished form across (primarily) go-glib and go-gst.

When we call GStreamer’s actual gst_element_register API, it turns to the GObject type system to build and interact with instances of our object.

So our first task will be registering our Go type with GObject.

We are going to be confronted with several limitations in CGO along the way that I’ll briefly summarize here for reference as they become relevant later.

- Go does not have a pre-processor

- C relies heavily on the use of macros, which are not actual “instructions” in the conventional sense. Instead they tell the compiler to “template” out symbols and instructions before compilation.

- We have

go generatewhich we will leverage later, but it is just a code generator. Users cannot use them as code in the same way as macros. They are expected to be executed beforehand by the user independently from the compiler.

- In addition to not having our own macros, we can’t use C macros from Go code (though sometimes we can get away with this depending on what the macro actually does).

- Go does not track any memory allocated by C.

- Because of this, we have to work against the garbage collector. Just because our GObject is present in the C “runtime” does not mean the Go runtime knows it needs to keep the Go instance around.

- Go pointers cannot be passed as arguments to C code.

- This includes functions. C code cannot directly execute anonymous Go functions or closures. They have to be statically defined.

- C cannot use types and structures defined in Go

We’ll go a little more in-depth into these issues, and how they were overcome, as we build out the ability to create a plugin in Go.

Defining the First Interface

Two features of GObjects that we will need to implement in Go-land are Inheritance and the GObject concept of Interfaces. To explain in a little more detail with context, we want our Go object to be able to do the following:

- Extend and/or inherit the capabilities of a GObject and its methods (e.g. a GstElement)

- Implement and declare GInterfaces (e.g. a GstUriHandler)

- Not die trying

The first Go interface we will lay down for this is the GoObjectSubclass.

In GObject world the GObjectClass is the structure that declares the properties and methods for the object.

It is the base class that all other subclasses must derive from, and the structure through which we inform the type system how to build our object as well as our inheritance and implementations.

We don’t have a need to separate the class from the object in Go land, so we will be able to lay these interfaces down directly on top of each other.

It will be the user’s responsibility to implement these interfaces in order to provide the necessary functionality and signal to the bindings what they are capable of.

The type system calls into these methods at the appropriate time during type registration and instantiation.

For starters we’ll want the user to implement at a minimum two methods for us (and we’ll show a little more depth on them later):

// GoObjectSubclass is an interface that abstracts on the GObjectClass. It is the minimum that should be implemented

// by Go types that get registered as GTypes.

type GoObjectSubclass interface {

// We'll be using the go object provided to us at registration, not as the object itself, but rather as an

// interface for creating new instances of the object when needed.

New() GoObjectSubclass

// ClassInit will be called on the object after it is registered with the type system. This is when the element

// will install its properties, methods, and any other metadata.

ClassInit(*ObjectClass)

}

The *ObjectClass passed to ClassInit above will be the go-bound representation of the GObjectClass that gets allocated for us during class initialization.

It is the structure through which we’ll be able to declare our capabilities with the type system.

Quick Primer on Promoted Methods in Go

The next interface we will need is not for the user to implement, persay, but rather for the developer binding whatever library they are working on to implement. We mentioned briefly before about how the GObject system provides method and class inheritance, but this is a feature we don’t have in Go strictly speaking. We do have the ability to declare embedded fields in a structure and obtain promoted methods from them, but that is not quite the same thing. Here is a short snippet to explain this concept in a little more detail.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

// A structure providing a single Do() method

type StructA struct{}

func (s *StructA) Do() { fmt.Println("Hello World") }

// Another structure that contains a single embedded member of StructA

// This is NOT inheritance even though it may look and seem like it.

type StructB struct{ *StructA }

func main() {

// Create an instance of StructA and call Do()

a := &StructA{}

a.Do()

// > Hello World

// Create an instance of StructB setting it's StructA member

// to the one we created above.

b := &StructB{a}

// Because of the single embedded field in our structure, Go is nice

// and gives us a promoted method of Do() that calls up to the StructA

// implementation. But we aren't actually "inheriting" this method.

// The compiler is just giving us a "shortcut" to it.

b.Do()

// > Hello World

}

Now let’s look at the same thing but with StructB defining its own Do() method.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

type StructA struct{}

func (s *StructA) Do() { fmt.Println("Hello World") }

type StructB struct{ *StructA }

func (s *StructB) Do() { fmt.Println("World Hello") }

func main() {

// Create an instance of StructA and call Do()

a := &StructA{}

a.Do()

// > Hello World

// Create an instance of StructB setting it's StructA member

// to the one we created above.

b := &StructB{a}

// Here we call StructB's implementation of Do. Which is not an override

// of StructA's, but rather an entirely new method ONLY on StructBs.

b.Do()

// > World Hello

// We did not actually override the Do() method. We have an embedded

// field of type StructA that automatically took on the name of the

// struct itself. And we have access to all of its properties as we

// do any other field in our struct.

b.StructA.Do()

// > Hello World

}

Where this is not compatible with how GObject operates, is in how the methods on these various structures get addressed. In C code using the GType system, it is common to take a pointer to an object that extends on several others, and coerce it to the implementation you are working with at that point in time. But that’s not the same as what Go is doing above with its promoted methods. To try to break this down a little bit more:

None of what I’m about to describe is even possible, but if it were the conversation would look a little like this

- Go says “Here take this

StructBinstance that extends onStructAbut doesDoits own way” - C says “Cool, I have this method here that needs a

StructAbut I’ll want toDoyour way” - Go says “Well crap, I can give you

StructA, but not like you want it. Here take my member” - C calls

Do()but does not call theStructBDolike it wanted to.

In the end when working strictly among code written in Go, you can pretend this is inheritance and parenting and it works more or less the same way in most use-cases. But for what we need to build out here, we can’t leverage any of the core elements of the Go type system. We’ll need to implement the behavior we want ourselves, and unfortunately it’s going to be a bit ugly. But the goal here is not for the bindings to avoid being ugly and unsafe. It’s for the user to not have to write ugly and unsafe code.

The Extendable Interface

At the end of the day, it is not so much code written in Go that needs to know about all of these “extendable” properties in other Go objects.

Go is statically typed, and every structure’s exposed properties and methods are documented and available to the caller.

What we do need to do, however, is let C know what’s what. And for that, I started with a new Go interface I called an Extendable.

// Extendable is an interface to be implemented by libraries binding other APIs. If a bound object

// builds upon the GObject system, the developer can also provide an implementation of this interface

// to be used during registration of a Go type. It exposes properties needed by the type registration

// system about the object being extended, and a method that should take some Go object implementation

// and link methods to the GObject subclass's vmethods at runtime.

type Extendable interface {

// Type should return the GType of the extended object

Type() Type // Type is another type provided by the go-glib bindings that wraps the GType

// ClassSize and InstanceSize should return the sizes for the structures belonging to the extended

// object. The type system will use these values to allocate memory for our object. This will be

// extended on a bit later.

ClassSize() int64

InstanceSize() int64

// InitClass will be called with the C pointer to the GObjectClass being created and a reference

// implementation of the extending Go object. This is not the same Go object that will be used by

// a calling application later on, but it CAN be used to inspect the methods implemented by the

// object. We'll have some fancy trickery later on around how we deal with matching an instance of

// a GObject at any point in time to the correct instance of the object from the Go runtime.

// Keep in mind, as we said earlier, C knows nothing of Go pointers, and Go knows nothing of C pointers.

InitClass(unsafe.Pointer, GoObjectSubclass)

}

The base object that all other objects extend from is the GObject.

So, the bindings will declare two additional items to provide that inheritance to the user.

- A “reference” interface containing the Go representation of the overridable methods (a little more on why I call this the “reference” interface later).

- An implementation of the

Extendableinterface that can be used with Go code registering a newGType.

First we’ll define a “reference” interface for the base extendable GType, the GObject. These method signatures match the spirit of their counterparts in the underlying GObjectClass.

// GoObject is an interface that abstracts on the GObject. In almost all cases at least SetProperty and GetProperty

// should be implemented by objects built from the go bindings. The Object passed to the following methods is the

// bound C GObject that corresponds to this instance.

type GoObject interface {

// SetProperty should set the value of the property with the given id. We'll explain properties a little more in-depth later on.

SetProperty(self *Object, id uint, value *Value)

// GetProperty should retrieve the value of the property with the given id.

GetProperty(self *Object, id uint) *Value

// Constructed is called when the Object has finished being set up.

Constructed(self *Object)

}

What’s important to note right now, is that not all of these methods are required to be overridden. When the user chooses not to override them, we want to inherit from the parent class.

If we tried to take a Go object that ONLY implements SetProperty and coerce it to this interface hoping to get some parent implementation or generic error for everything else, we’d get a runtime panic.

In the same respect, we can’t take some arbitrary pointer to a go structure, and coerce it to a structure it isn’t.

So when setting up the GObjectClass we’ll have to cherry pick only the methods that the Go object chose to implement.

It’s for this reason that I refer to this as the reference interface. The bindings aren’t actually going to use it in practice and it primarily serves as documentation for the user.

There are likely other ways this could have been implemented, but ultimately I think the amount of boilerplate required would have been the same.

Next we need the Extendable implementation that can be paired with a Go object implementing parts of this interface.

/*

#include "glib.go.h"

// C prelude...

*/

import "C"

// ExtendsObject signifies a GoElement that extends a GObject. It is the base Extendable

// that all other implementations should derive from.

var ExtendsObject Extendable = &extendObject{}

type extendObject struct{}

// Type returns the GType for a GObject

func (e *extendObject) Type() Type { return Type(C.g_object_get_type()) }

// We won't actually be creating our own C structure to store fields relating to the

// Go object. Rather we will utilize the private data already included in the GObject

// later on. So for the size of our structures, we just declare those of the structures

// we descend from.

// In CGO, the size of any structure or type can be obtained with C.sizeof_name

func (e *extendObject) ClassSize() int64 { return int64(C.sizeof_GObjectClass) }

func (e *extendObject) InstanceSize() int64 { return int64(C.sizeof_GObject) }

func (e *extendObject) InitClass(klass unsafe.Pointer, elem GoObjectSubclass) {

// Set up the GObjectClass at klass with the methods provided by elem.

// We'll disect this piece more in a bit.

}

When another binding library wants to extend on the ExtendsObject they can do something like this:

var ExtendsAnotherObject Extendable = &extendsAnotherObject{ExtendsObject}

type extendsAnotherObject struct { parent Extendable }

func (e *extendsAnotherObject) InitClass(klass unsafe.Pointer, elem GoObjectSubclass) {

// Call up to the parent InitClass

e.parent.InitClass(klass, elem)

// Continue class initialization

// ...

}

We’ll continue talking about the InitClass method more later after we’ve registered the GType.

Registering the Type

At this point we’ve laid down enough boilerplate to register the type.

We still have not covered how we handle objects implementing a GInterface, but this is not required to get started with what we have so far.

We’ll come back and tweak this a little more later once we add the support for Interfaces.

First we’ll declare some global variables to help us with this process and a new structure where we will store data about the type we are registering.

// Declare a global map where we will track Go types that have already been registered

// to a GType. This could also be accomplished with a sync.Once, but at the time I wanted

// the ability to easily grab a GType without having to call into the C system with some

// instantiated object.

var registeredTypes map[string]Type

// Declare a mutex so we do not try to register multiple types at the same time, and potentially

// corrupt our map.

var registerMutex sync.Mutex

// This is a structure where we will store data to be given back to us by the GObject callbacks.

// We'll explain this a little more below.

type classData struct {

elem GoObjectSubclass

ext Extendable

}

The next thing we need to build out for the user is the GTypeInfo to register with the type system. This structure contains a series of callbacks that get executed during class and instance initialization and finalization. We won’t be needing all of the initializers, or any of the finalizers, primarily because we will be managing most of our Go memory via the Go runtime and its finalizers.

What we’d like to do is define the necessary callbacks in Go such that they can interact with the appropriate Go types, and use those to initialize what’s needed for the Go runtime. It’s here where we begin to run into some of our challenges with CGO. Remember when we said that Go pointers cannot be passed as arguments to C code? Well that would seem to be a nail in the coffin for accomplishing this, but we do have some workarounds.

The first thing CGO lets us do that we can use to get over this hurdle, is in a separate file define Go functions and export them to C. This is also how we’d typically export methods that we want to be available in our shared library, and we’ll see it used for that at the end. Due to the way CGO pre-processes source files, we have to keep these functions separate from the C code that uses it. How we use them from C code we can get to after, but the way you do this is pretty simple:

package glib

// #include <glib/glib.h>

import "C"

//export myGoCallback

func myGoCallback(someCPtr C.gpointer) {

someGoFunction()

// ...

}

The export comment above the function along with the “C” import, tells the compiler to export that method as a C symbol.

We can also use this function from our own C code within the package it’s defined.

We just can’t use the function itself as a value for a callback, nor can we reference it directly from the Go runtime a la C.myGoCallback.

To get around this limitation, we can import the Go function into our own C code, and define a C function that simply calls back to the Go function with the parameters it’s given.

#include <glib/glib.h>

extern void myGoCallback (gpointer somePtr);

void

myCGOCallback (gpointer somePtr) {

myGoCallback(somePtr);

}

Now from our Go code we can address a callback to C.myCGOCallback and our callback defined in Go will be invoked with the parameters it receives.

We’ll end up using this idiom a lot since the GObject system, as well as most derivative libraries, relies heavily on the use of callbacks.

Another common convention in callbacks when used by the GObject libraries is to pass optional userdata to the user-defined callbacks. This is useful for many things. For example, if what we want the bindings to actually do is call into some anonymous function or closure the user has provided us. Or, which is about to be the case for us, we want to be able to reference some structure we allocated in Go before the callback was invoked. We’ve overcome our issue with using Go functions as callbacks, but we have now bumped into another one of our CGO limitations, further limited by how we just overcame the last one.

We cannot pass go pointers to C functions, but we just had to declare a C callback to even get to our Go callback. So now, we can’t pass this arbitrary Go data to our callback because it is defined in C.

On top of this, Go does not track any memory allocated by C. That means we can’t just take the address of the go data, give it to C, and hope the object hasn’t been garbage collected when the callback actually gets executed. Chances are eventually, we’d wind up with a pointer to nowhere when we actually want to use it.

Thankfully, and as a testament to how big things can come in small packages, there is mattn’s go-pointer package for just this purpose. What this package does is provide us with three very simple methods for handling Go structures that we want to pass back and forth from C.

Save(interface{}): This method allocates a dummy C pointer, saves it to an internal map of pointers to go interfaces along with the given go value, and returns the dummy C pointer for consumption.- Saving a reference to the interface in the global Go runtime keeps the garbage collector from attempting to dispose of it.

Restore(unsafe.Pointer): This method will take a dummy C pointer, and return the Go interface that matches it in the internal map.Unref(unsafe.Pointer): Frees the dummy C pointer and removes the key from the internal map (thus letting the Go garbage collector scrape it up)

With all of the above accounted for and taken care of, we can now register the Go type to the GType system.

import gopointer "github.com/mattn/go-pointer"

// RegisterGoType will register a given interface extending the Extendable with the given name.

// The GType that gets registered to the object is returned.

func RegisterGoType(name string, elem GoObjectSubclass, extendable Extendable) Type {

registerMutex.Lock()

defer registerMutex.Unlock()

// If we've already registered this type, return the Type we have

if registered, ok := registeredTypes[reflect.TypeOf(elem).String()]; ok {

return registered

}

// Create a dummy C pointer pointing to the information about the Go object

// and the go implementations for the Objects it intends to extend.

//

// We'll retrieve this pointer during class_init later.

ptr := gopointer.Save(&classData{

elem: elem,

ext: extendable,

})

// Allocate a new GTypeInfo. We can free this immediately since the type

// system remembers the pointers to the methods it needs.

typeInfo := (*C.GTypeInfo)(C.malloc(C.sizeof_GTypeInfo))

defer C.free(unsafe.Pointer(typeInfo))

// These are the fields and vmethods in the type information that

// we are not concerned with. Set them to their zero or nil values.

typeInfo.base_init = nil

typeInfo.base_finalize = nil

typeInfo.class_finalize = nil

typeInfo.n_preallocs = 0

typeInfo.value_table = nil

// As we mentioned earlier, there isn't a need to store much information

// in the C object that will represent our Go type. So we take the size

// properties from the Extendable and use those, assuming we, at the very

// least, need space for all the vmethods provided by the extended class.

//

// Libraries that want to provide GObjects AND methods for bindings in other

// languages will have to both implement their Extendable as well as define

// the neccessary C structures for the Type system and those languages to infer

// from. These sizes would reflect the size of those C structures.

typeInfo.class_size = C.gushort(extendable.ClassSize())

typeInfo.instance_size = C.gushort(extendable.InstanceSize())

// Set the class_init function to our go classInit callback. C.cgoClassInit

// follows the idiom shown above with callbacks. We'll show the definition

// of this method next.

typeInfo.class_init = C.GClassInitFunc(C.cgoClassInit)

typeInfo.class_data = (C.gconstpointer)(ptr) // Our dummy C pointer to the Go class data

// Similar for the class_init, this is the method that gets called to create new instances

// of our Go object. There is no userdata passed to this function, so we'll track globally

// GObjectClass's when they are registered to the go types where we have a New() method already

// to create fresh instances.

typeInfo.instance_init = C.GInstanceInitFunc(C.cgoInstanceInit)

// We need to convert the Go string into a NULL terminated C char array

// and again free it immediately when we are done.

cName := C.CString(name)

defer C.free(unsafe.Pointer(cName))

// Register and return the new GType

gtype := C.g_type_register_static(

C.GType(extendable.Type()),

(*C.gchar)(cName),

typeInfo,

C.GTypeFlags(0),

)

// Write the new type to our global map

registeredTypes[reflect.TypeOf(elem).String()] = Type(gtype)

// Return the GType to caller

return Type(gtype)

}

The two callbacks we used here are goClassInit and goInstanceInit, which were actually referenced as C trampolines following the extern idiom described above.

We are going to utilize a second global map similar to the registeredTypes one called registeredClasses that looks like this.

// A map of a gpointer pointing to the GObjectClass representing the GoObjectSubclass value

// We will use this information when performing class_init and instance_init

var registeredClasses = map[C.gpointer]GoObjectSubclass

And below are the go callbacks. First the goClassInit which will only be called once when the class is being registered with the type system.

//export goClassInit

func goClassInit(klass C.gpointer, klassData C.gpointer) {

registerMutex.Lock()

defer registerMutex.Unlock()

// Grab the dummy C pointer that references the classData we created in the go runtime

ptr := unsafe.Pointer(klassData)

// Coerce that interface back to a classData structure. This is unsafe, but since these

// methods are not exported for external consumption, their usage is constrained to the

// flows defined in this package.

data := gopointer.Restore(ptr).(*classData)

// We won't need the dummy C pointer after this and we can safely clean it up

defer gopointer.Unref(ptr)

// The pointer we were given above is the same pointer that will be given to us everytime

// we want to create a new instance of our Go object. So we save a reference of it to the

// Go object containing a New() method we can utilize.

registeredClasses[klass] = data.elem

// During class initialization we can declare to the type system that we have private

// data we'd like to store along with instances of our object. This will be very useful

// for us as we'll see in the instance_init callback. For now, we declare that we are

// going to save a uintptr to the private data of the object. This pointer will be a

// reference to the Go object matching the instantiated object.

C.g_type_class_add_private(klass, C.gsize(unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0))))

// Run the InitClass method provided by the Extendable that was given at Type registration

// This is when vmethod assignment will take place, which we will cover in the next section.

data.ext.InitClass(unsafe.Pointer(klass), data.elem)

// Call the Go Object's ClassInit method, giving it a chance to register any additional properties

// it has.

data.elem.ClassInit(wrapObjectClass(klass)) // Wraps the GObjectClass into a go-bound ObjectClass

}

Finally is the function that will be called during instance_init, which is to say when new instances of our object are being created.

//export goInstanceInit

func goInstanceInit(obj *C.GTypeInstance, klass C.gpointer) {

registerMutex.Lock()

defer registerMutex.Unlock()

// Create a new instance of the GoObject from the interface we saved globally

// during class_init.

goelem := registeredClasses[klass].New()

// Determine the name of the Go type so we can query our registeredTypes for the cooresponding

// GType.

typeName := reflect.TypeOf(registeredClasses[klass]).String()

// Create a dummy C pointer pointing to the new go object

ptr := gopointer.Save(goelem)

// We retrieve the address to the private data that we allocated during class_init,

// and then save the dummy C pointer value to it. When retrieving the Go implementation of

// a C vmethod, we'll use this value to determine who the Go caller should be.

private := C.g_type_instance_get_private(obj, C.GType(registeredTypes[typeName]))

C.memcpy(unsafe.Pointer(private), unsafe.Pointer(&ptr), C.gsize(unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0))))

}

When we want to get the reference to the Go object back from some arbitrary instantiated GObject, we can use a function like this:

func privateFromObj(obj unsafe.Pointer) unsafe.Pointer {

// Retrieve the address to the private data inside the object. objectGType is a simple wrapper

// around the glib macro for determining an object's type. Remmber, how we can't use macros in Go code?

private := C.g_type_instance_get_private((*C.GTypeInstance)(obj), C.objectGType((*C.GObject)(obj)))

if private == nil {

return nil

}

// Coerce the value we got back to what we actually put there, which is a pointer to a pointer.

// In writing this out I realize it might not be necessary to have it be a pointer to a pointer,

// and instead we *could* just store the pointer value directly.

privAddr := (*unsafe.Pointer)(unsafe.Pointer(private))

if privAddr == nil {

return nil

}

// However, since it's a pointer to a pointer, we dereference it back to the dummy C pointer that it is

return *privAddr

}

The output of this function can be passed to gopointer.Restore() to get back the reference to the underlying Go type.

Back to that InitClass Function

A lot of what we learned just now with regards to C callbacks and Go pointers, coupled with how we are building our Go objects at runtime,

provides a little more context which will help us understand how the InitClass methods provided by the Extendable implementations works.

Let’s first take a look at the implementation provided for the ExtendsObject

func (e *extendObject) InitClass(klass unsafe.Pointer, elem GoObjectSubclass) {

C.setGObjectClassFinalize(klass)

if _, ok := elem.(interface {

SetProperty(obj *Object, id uint, value *Value)

}); ok {

C.setGObjectClassSetProperty(klass)

}

if _, ok := elem.(interface {

GetProperty(obj *Object, id uint) *Value

}); ok {

C.setGObjectClassGetProperty(klass)

}

if _, ok := elem.(interface {

Constructed(*Object)

}); ok {

C.setGObjectClassConstructed(klass)

}

}

Earlier we mentioned how it is not required by the type system to override every vmethod provided by the extended class. When we chose not to do so, we inherit the behavior of the parent class.

To emulate this, we can leverage Go’s ability to check if any arbitrary interface implements another one (even one declared in-line to save us from even more boilerplate 😉).

We use this to iterate on every possible method that can be implemented by extending objects (as per our “reference” implementation) and then call into C to override only the appropriate methods on the GObjectClass.

Let’s look at the C definitions for these setters, and then we’ll look at the backing Go implementations that get invoked either by the trampolines or directly.

#include "glib.go.h"

/*

Exported go methods that we will show next

*/

extern void goObjectSetProperty (GObject * object, guint property_id, const GValue * value, GParamSpec *pspec);

extern void goObjectGetProperty (GObject * object, guint property_id, GValue * value, GParamSpec * pspec);

extern void goObjectConstructed (GObject * object);

extern void goObjectFinalize (GObject * object, gpointer klass);

/*

The function called when an instance of our object is destroyed. We don't actually let the user

supply this logic, and instead handle finalization logic inside the bindings.

*/

void objectFinalize (GObject * object)

{

GObjectClass *parent = g_type_class_peek_parent((G_OBJECT_GET_CLASS(object)));

goObjectFinalize(object, G_OBJECT_GET_CLASS(object));

parent->finalize(object);

}

/*

The function called when a new instance of our object has finished being constructed. Call the go callback

and chain up to the parent handler.

*/

void objectConstructed (GObject * object)

{

GObjectClass *parent = g_type_class_peek_parent((G_OBJECT_GET_CLASS(object)));

goObjectConstructed(object);

parent->constructed(object);

}

/*

set_property and get_property are set directly to the exported go functions, no parent logic is required

*/

void setGObjectClassSetProperty (void * klass) { ((GObjectClass *)klass)->set_property = goObjectSetProperty; }

void setGObjectClassGetProperty (void * klass) { ((GObjectClass *)klass)->get_property = goObjectGetProperty; }

/*

These methods need to chain up to the parent, and so we call into our C functions above that do that on top

of calling into the go callback.

*/

void setGObjectClassConstructed (void * klass) { ((GObjectClass *)klass)->constructed = objectConstructed; }

void setGObjectClassFinalize (void * klass) { ((GObjectClass *)klass)->finalize = objectFinalize; }

Now let’s look at the cooresponding Go functions. We’ll cover a few helpers and just two of the callbacks, as they all follow the same pattern.

// This function further wraps the privateFromObj method we defined above.

// It takes a pointer to a GObject, retrieves the dummy C pointer we stored

// in the private data, and restores it back to the Go object.

func fromObjectUnsafePrivate(obj unsafe.Pointer) GoObjectSubclass {

objPriv := privateFromObj(obj)

ptr := gopointer.Restore(objPriv)

goclass := ptr.(GoObjectSubclass)

return goclass

}

//export goObjectFinalize

func goObjectFinalize(obj *C.GObject, klass C.gpointer) {

// Not much here, we just Unref our dummy C pointer and let the Go garbage collector take care

// of the go structures.

gopointer.Unref(privateFromObj(unsafe.Pointer(obj)))

}

// SetProperty and GetProperty follow the same pattern as the Constructed. As do all other methods

// that can be overridden by an extending object. The bindings provide a helper method for auomatically

// giving you back the wrapped object and matching Go instance, but it is written out above and here

// for documentation purposes.

//export goObjectConstructed

func goObjectConstructed(obj *C.GObject) {

// simple wrapper that wraps the GObject in the binding equivalent

object := wrapObject(obj)

// Retrieve the go object from the GObject's private data

goObject := fromObjectUnsafePrivate(unsafe.Pointer(obj))

// Coerce the Go object to an interface with a Constructed method and execute it.

// We don't have to do any safety checks here, because we only assigned the vmethod

// on the GObectClass if the Constructed method was implemented on the Go type already.

goObject.(interface{ Constructed(*Object) }).Constructed(object)

}

The InitClass of every Extendable follows an almost identical pattern. Chain up to the parent InitClass, check each possible vmethod’s existence on the Go type, and assign trampolines to the vmethods on the GObjectClass.

Registering GInterfaces to the GType

Much of what we learned and had to do for class initialization will be relevant to providing one or more GInterfaces along with our Go object.

But first, we’ll need another interface for binding libraries to implement very similar to the Extendable, as well as a data structure we’ll pass around when the C equivalent gets called.

// TypeInstance is a loose binding around the glib GTypeInstance. It holds the information required to assign

// various capabilities of a GoObjectSubclass.

type TypeInstance struct {

// The GType cooresponding to this GoType

GType Type

// A pointer to the underlying C instance being instantiated.

GTypeInstance unsafe.Pointer

// A representation of the GoType.

GoType GoObjectSubclass

}

// Interface can be implemented by extending packages. They provide the base type for the interface and

// a function to call during interface_init.

//

// The function is called during class_init and is passed a TypeInstance populated with the GType

// corresponding to the Go object, a pointer to the underlying C object, and a pointer to a reference

// Go object. When the object is actually used, a pointer to it can be retrieved from the C object with

// fromObjectUnsafePrivate shown above.

//

// The user of the Interface is responsible for implementing the methods required by the interface. The GoType

// provided to the InterfaceInitFunc will be the object that is expected to carry the implementation.

type Interface interface {

Type() Type

Init(*TypeInstance)

}

We then alter our RegisterGoType function to take an arbitrary number of Interfaces during registration.

func RegisterGoType(name string, elem GoObjectSubclass, extendable Extendable, interfaces ...Interface)

And right before returning we loop over those interfaces and follow a familiar pattern

// ...

// The structure we will pass as the userdata to the interface_init callback

type interfaceData struct {

iface Interface

gtype Type

classData *classData

}

// ...

for _, iface := range interfaces {

// Create our dummy C pointer

gofuncPtr := gopointer.Save(&interfaceData{

iface: iface,

gtype: Type(gtype),

classData: classData,

})

// Create an ifaceinfo assigned to a trampoline defined below

ifaceInfo := C.GInterfaceInfo{

interface_data: (C.gpointer)(unsafe.Pointer(gofuncPtr)),

interface_finalize: nil,

interface_init: C.GInterfaceInitFunc(C.cgoInterfaceInit),

}

// Register the interface with the GType

C.g_type_add_interface_static(

(C.GType)(gtype),

(C.GType)(iface.Type()),

&ifaceInfo,

)

}

Our exported goInterfaceInit is pretty simple and looks like this.

//export goInterfaceInit

func goInterfaceInit(iface C.gpointer, ifaceData C.gpointer) {

// Restore the go pointer

ptr := unsafe.Pointer(ifaceData)

defer gopointer.Unref(ptr)

// Call the interface init handler in this data

data := gopointer.Restore(ptr).(*interfaceData)

data.iface.Init(&TypeInstance{

GoType: data.classData.elem,

GType: data.gtype,

GTypeInstance: unsafe.Pointer(iface),

})

}

To bring this all together let’s look at the GstUriHandler interface implementation in go-gst. Most of these idioms should be recognizable at this point.

First, we have the C code that contains our trampolines back to our go exports.

/* Our exported go functions */

extern GstURIType goURIHdlrGetURIType (GType type);

extern const gchar * const * goURIHdlrGetProtocols (GType type);

extern gchar * goURIHdlrGetURI (GstURIHandler * handler);

extern gboolean goURIHdlrSetURI (GstURIHandler * handler,

const gchar * uri,

GError ** error);

/* Sets the vmethods on the interface to our go exports */

void uriHandlerInit (gpointer iface, gpointer iface_data)

{

((GstURIHandlerInterface*)iface)->get_type = goURIHdlrGetURIType;

((GstURIHandlerInterface*)iface)->get_protocols = goURIHdlrGetProtocols;

((GstURIHandlerInterface*)iface)->get_uri = goURIHdlrGetURI;

((GstURIHandlerInterface*)iface)->set_uri = goURIHdlrSetURI;

}

Followed by the implementation of the Interface interface we declared earlier.

// InterfaceURIHandler represents the GstURIHandler interface GType. Use this when querying bins

// for elements that implement a URIHandler, or when signaling that a GoObjectSubclass provides this

// interface. Note that the way this interface is implemented, it can only be used once per plugin.

var InterfaceURIHandler glib.Interface = &interfaceURIHandler{}

type interfaceURIHandler struct{ glib.Interface }

func (i *interfaceURIHandler) Type() glib.Type { return glib.Type(C.GST_TYPE_URI_HANDLER) }

func (i *interfaceURIHandler) Init(instance *glib.TypeInstance) {

C.uriHandlerInit((C.gpointer)(instance.GTypeInstance), nil)

}

And finally, for an example of one of the exported Go functions.

//export goURIHdlrGetURI

func goURIHdlrGetURI(hdlr *C.GstURIHandler) *C.gchar {

// Get our go object from the private data in the instance

goObject := fromObjectUnsafePrivate(unsafe.Pointer(hdlr))

// Coerce the go object to the URIHandler interface (not shown here)

// and execute the method.

uri := goObject.(URIHandler).GetURI()

if uri == "" {

return nil

}

// Convert the return from the go function to a C type and return it

// to the caller

return (*C.gchar)(unsafe.Pointer(C.CString(uri)))

}

Registering the Plugin with GStreamer

That was a lot of work to get to this point, but everything is now in place for the user to take some arbitrary Go structure and declare it as a GType.

From here, we operate under the assumption that an Extendable exists for the GstBaseSrc that descends from and is implemented the same way as the ExtendsObject.

The binding for the gst_element_register API is pretty simple.

// RegisterElement creates a new elementfactory capable of instantiating objects of the given GoElement

// and adds the factory to the plugin. A higher rank means more importance when autoplugging.

func RegisterElement(plugin *Plugin, name string, rank Rank, elem glib.GoObjectSubclass, extends glib.Extendable, interfaces ...glib.Interface) bool {

return gobool(C.gst_element_register(

plugin.Instance(),

C.CString(name),

C.guint(rank),

C.GType(glib.RegisterGoType(name, elem, extends, interfaces...)), // Register the GType for the go object on the fly

// which will go through all the boilerplate we laid

// down earlier.

))

}

But how we get to this point is a little trickier, and is where I ultimately ended up writing a Go generator purely out of trying to provide the best UX possible.

When GStreamer loads our .so file, it looks for a symbol matching the following format: gst_plugin_NAME_get_desc.

They make this very easy to do for the person developing their own plugin. They provide a GST_PLUGIN_DEFINE macro that handles all the boilerplate instructions necessary.

What it then can expect this function to do is return a GstPluginDesc that, along with metadata, contains an init function for GStreamer to call that performs the actual registration.

But remember how we can’t use C macros from Go code? And how we don’t have any pre-processor?

Creating a function that can convert between the example we showed at the top of this article and what GStreamer needs is pretty simple, but again we’ll have to annoy memory-leak checkers.

First, some more C boilerplate.

#include "gst.go.h"

/* More exported callbacks */

extern gboolean goGlobalPluginInit (GstPlugin * plugin);

gboolean

cgoGlobalPluginInit(GstPlugin * plugin)

{

return goGlobalPluginInit(plugin);

}

GstPluginDesc * getPluginMeta (gint major,

gint minor,

gchar * name,

gchar * description,

GstPluginInitFunc init,

gchar * version,

gchar * license,

gchar * source,

gchar * package,

gchar * origin,

gchar * release_datetime)

{

GstPluginDesc * desc = malloc ( sizeof (GstPluginDesc) );

desc->major_version = major;

desc->minor_version = minor;

desc->name = name;

desc->description = description;

desc->plugin_init = init;

desc->version = version;

desc->license = license;

desc->source = source;

desc->package = package;

desc->origin = origin;

desc->release_datetime = release_datetime;

return desc;

}

And the go types representing the GstPluginDesc.

// PluginMetadata represents the information to include when registering a new plugin

// with gstreamer.

type PluginMetadata struct {

// The major version number of the GStreamer core that the plugin was compiled for, you can just use VersionMajor here

MajorVersion Version

// The minor version number of the GStreamer core that the plugin was compiled for, you can just use VersionMinor here

MinorVersion Version

// A unique name of the plugin (ideally prefixed with an application- or library-specific namespace prefix in order to

// avoid name conflicts in case a similar plugin with the same name ever gets added to GStreamer)

Name string

// A description of the plugin

Description string

// The function to call when initiliazing the plugin

Init PluginInitFunc

// The version of the plugin

Version string

// The license for the plugin, must match one of the license constants in this package

License License

// The source module the plugin belongs to

Source string

// The shipped package the plugin belongs to

Package string

// The URL to the provider of the plugin

Origin string

// The date of release in ISO 8601 format.

// See https://gstreamer.freedesktop.org/documentation/gstreamer/gstplugin.html?gi-language=c#GstPluginDesc for more details.

ReleaseDate string

}

// Export will export the PluginMetadata to an unsafe pointer to a GstPluginDesc.

func (p *PluginMetadata) Export() unsafe.Pointer {

globalPluginInit = p.Init

desc := C.getPluginMeta(

C.gint(p.MajorVersion),

C.gint(p.MinorVersion),

(*C.gchar)(unsafe.Pointer(&[]byte(p.Name)[0])),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(p.Description)),

(C.GstPluginInitFunc(C.cgoGlobalPluginInit)),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(p.Version)),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(string(p.License))),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(p.Source)),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(p.Package)),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(p.Origin)),

(*C.gchar)(C.CString(p.ReleaseDate)),

)

return unsafe.Pointer(desc)

}

It is in that Export method where we abandon all hope of freeing all those C strings we generated.

But knowing that any self respecting kernel will handle necessary cleanup after the process exits, and with no sensitive data being present in these fields, we can live with ourselves.

But with the above all done, the complete entrypoint to the plugin can be finished.

To grab from the generated code for the example gofilesrc:

// !WARNING! THIS FILE WAS GENERATED BY GST-PLUGIN-GEN !WARNING! //

package main

import "C"

import (

"unsafe"

"github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst/gst"

"github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst/gst/base"

)

// The metadata for this plugin

var pluginMeta = &gst.PluginMetadata{

MajorVersion: gst.VersionMajor,

MinorVersion: gst.VersionMinor,

Name: "gofilesrc",

Description: "File plugins written in go",

Version: "v0.0.1",

License: gst.LicenseLGPL,

Source: "go-gst",

Package: "examples",

Origin: "https://github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst",

ReleaseDate: "2021-01-04",

// The init function is called to register elements provided by the plugin.

Init: func(plugin *gst.Plugin) bool {

return gst.RegisterElement(

plugin,

// The name of the element

"gofilesrc",

// The rank of the element

gst.RankNone,

// The GoElement implementation for the element

&fileSrc{},

// The base subclass this element extends

base.ExtendsBaseSrc,

// The interfaces this element implements

gst.InterfaceURIHandler,

)

},

}

// A single method must be exported from the compiled library that provides for GStreamer

// to fetch the description and init function for this plugin. The name of the method

// must match the format gst_plugin_NAME_get_desc, where NAME is the name of the compiled

// artifact with or without the "libgst" prefix and hyphens are replaced with underscores.

//export gst_plugin_gofilesrc_get_desc

func gst_plugin_gofilesrc_get_desc() unsafe.Pointer { return pluginMeta.Export() }

I did not want the user to have to import “C” at all, though. So this is where I surrendered to writing a go generator. Doing so is not terribly difficult, and we have a very simple code structure we are working with. You can see the full code for the generator here, but what’s important is what we exposed to the user for generating the above.

//go:generate gst-plugin-gen

//

// +plugin:Name=gofilesrc

// +plugin:Description=File plugins written in go

// +plugin:Version=v0.0.1

// +plugin:License=gst.LicenseLGPL

// +plugin:Source=go-gst

// +plugin:Package=examples

// +plugin:Origin=https://github.com/tinyzimmer/go-gst

// +plugin:ReleaseDate=2021-01-04

//

// +element:Name=gofilesrc

// +element:Rank=gst.RankNone

// +element:Impl=fileSrc

// +element:Subclass=base.ExtendsBaseSrc

// +element:Interfaces=gst.InterfaceURIHandler

//

package main

From there all that’s left to the user is implementing the methods on the Extendables and Interfaces they declared.

I won’t show all of the code for the plugin here and you can see it in its entirety in git.

But, it leverages the above which is all included now across the go-gst and go-glib bindings, and just to show the methods required by the GoObjectSubclass.

// The structure where we are defining our methods. Contains private fields

// for structures holding the current settings and state.

type fileSrc struct {

// The settings for the element

settings *settings

// The current state of the element

state *state

}

// When New() is called we return a new instance of the fileSrc structure.

func (f *fileSrc) New() glib.GoObjectSubclass {

return &fileSrc{

settings: &settings{},

state: &state{},

}

}

// We call into the various bindings across go-gst and go-glib to declare the metadata

// and pads associated with our element.

func (f *fileSrc) ClassInit(klass *glib.ObjectClass) {

class := gst.ToElementClass(klass)

class.SetMetadata(

"File Source",

"Source/File",

"Read stream from a file",

"Avi Zimmerman <avi.zimmerman@gmail.com>",

)

class.AddPadTemplate(gst.NewPadTemplate(

"src",

gst.PadDirectionSource,

gst.PadPresenceAlways,

gst.NewAnyCaps(),

))

class.InstallProperties(properties) // Properties contains GParamSpec bindings that were not covered in this article

}

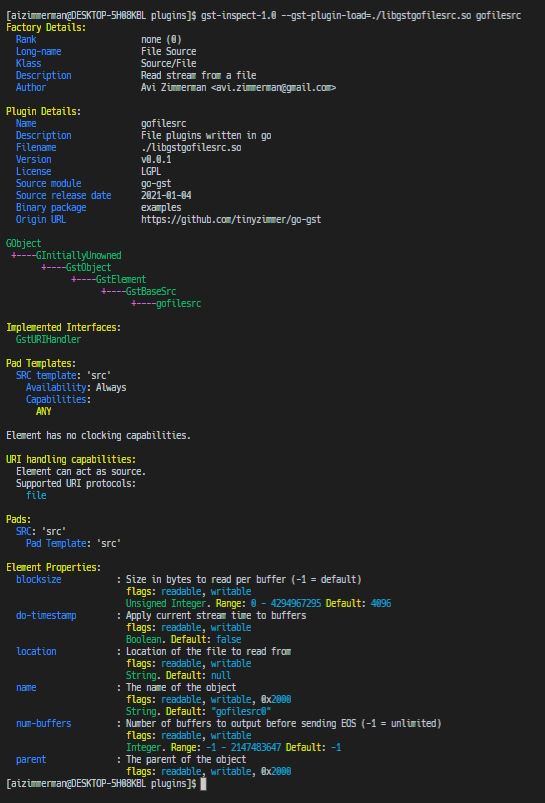

And when all is said and done and compiled…

One thing that is not yet implemented yet in the bindings is the ability to define Signals. User’s currently have the ability to emit and connect to existing ones on objects, but they are unable to declare their own. This will be addressed in a future release.

That’s all I’ve got for this post, I hope you found it interesting. Maybe some of the roundabout adventures taken here will reach the Go developers and they’ll come up with new ideas on how to further improve the CGO ecosystem. It is very powerful the way it is now, but the introduction of things such as Generics in Go v2 (if that is actually seen to fruition) could open some new and exciting doors for how this all could be implemented in the future.

Thanks for reading! 😄